[This essay was an attempt to summarize my findings for a more general audience in the spirit of the “Capitalism and the Myth of Maximizing” book manuscript I was also working on. The title and some of the content I had worked out in my RELACS presentation of March 1999. If I had finished the article, I intended to submit it to the American Historical Review.]

Historians since the turn of the 20th century have argued back and forth over whether 17th-century Virginians could better be seen as traditional Englishmen or modern Americans. Cultural and intellectual historians have made the case that these tobacco planters were far closer to traditional Englishmen, motivated primarily by the desire to achieve gentility in the manner of the English landed classes. Social historians, on the other hand, have argued that these planters were far closer to modern Americans, far more interested in looking out for number one than achieving gentility.

But have agreed on at least one thing: 17c Virginians were maximizers. I challenge this way of looking at 17th-century Virginians through an analysis of their actual economic behavior. I think that these findings are quite significant and will force us to revise the way we teach the seventeenth-century Chesapeake in the American history survey. But I believe my findings have even broader implications. The study of economic behavior I believe will force us to rethink standard assumptions about the economic motivation and behavior of early Americans in general, and in particular that of antebellum cotton planters who shared so much in common with 17th-century tobacco planters. [discussion of monoculture]

Interestingly, whatever their differences over the traditional or modern mindset of seventeenth-century Virginians, historians have never doubted for a minute that these planters were industrious maximizers par excellence‑-taking advantage of every reasonable opportunity to maximize income‑-whether because of the need to accumulate wealth in order to purchase the material requisites of gentility; the struggle to survive and raise a family on a rugged frontier; or simply entrepreneurial drive.

It is truly amazing that this image of industrious maximizers has persisted for so long unquestioned because the image has fundamental flaws. Indeed, logic, theory, and empirical evidence all point in the opposite direction that 17th-century Virginians were anything but industrious maximizers.

Let’s first look at the problems of internal logic in recent colonial Chesapeake historiography. Since the 1970s most of this scholarship has been directly or indirectly influenced by staples theory, a theory borrowed from neo-classical economists that emphasizes the export-led nature of colonial economic and demographic development. Followers of staples theory believe that planters were neoclassical economic men responding to rising tobacco prices by increasing demand for the factors of production (labor, land, capital) which over time led to increased tobacco production. Historians like Rus Menard, John McCusker, Paul Clemens, Gloria Main, and Allan Kulikoff, under the aegis of staples theory, have all highlighted a cyclical pattern of booms and busts throughout the seventeenth century as planters alternately expanded production in response to higher tobacco prices and contracted production in response to falling prices.

The strongest behavioral challenge to this boom-bust interpretation among Chesapeake scholars has come from Darrett and Anita Rutman and their student Charles Wetherell. They’re not great fans of staples theory, aligning themselves instead with the alternative “Malthusian-frontier” interpretation of early American economic and demographic development, which stresses the central importance of autonomous demographic forces rather than staple exports. The Rutmans emphasize the inelastic response of planters to changing tobacco prices: rising tobacco prices had little impact on industrious planters already maximizing production. This need for planters to constantly maximize, they suggest, stems ultimately from the struggle to survive in the New World wilderness and provide for the next generation, but they also note that maximizing tobacco production was a traditional strategy that planters maintained despite the vagaries of the market because there were no seemingly more profitable alternatives without undertaking great risk and uncertainty. 1

Both these groups of historians present little in the way of hard evidence to support their arguments. Indeed the one bit of relevant empirical evidence on tobacco productivity they do present hardly seems to provide solid support for either the staples or the Rutman argument. For tobacco productivity actually rose during the seventeenth century while tobacco prices were falling. Figure 1 is a plot of tobacco productivity (in pounds per tithable) and tobacco prices. The stars are productivity and the diamonds are prices. As you can see, as the price of tobacco went down, productivity rose across the 17th century. The data on this figure are based on aggregate English tobacco import and tithable population data, but the same trends of rising productivity in the 17th century are suggested by contemporary literary estimates and analysis of probate records. Although how much a man could or did make varied widely from place to place, year to year, man to man, behind this variance seems to lie a distinct inverse relationship between the trends in productivity and the trends in tobacco prices across the seventeenth century. 2 The lower the price the more they made.

Historians have not very successfully incorporated such behavioral evidence into their models. Staples theorists have been forced into the uncomfortable position of suggesting that planters responded to good times and bad times in the same way, with ever-expanding tobacco production every time prices fell or rose, pushed during busts and pulled during booms. The Rutmans have similarly paradoxically suggested that supposedly maximizing planters responded to falling tobacco prices by increasing production. 3 I would suggest that such problematic interpretations stem directly from the a priori assumption that 17th-century Virginians were industrious maximizers.

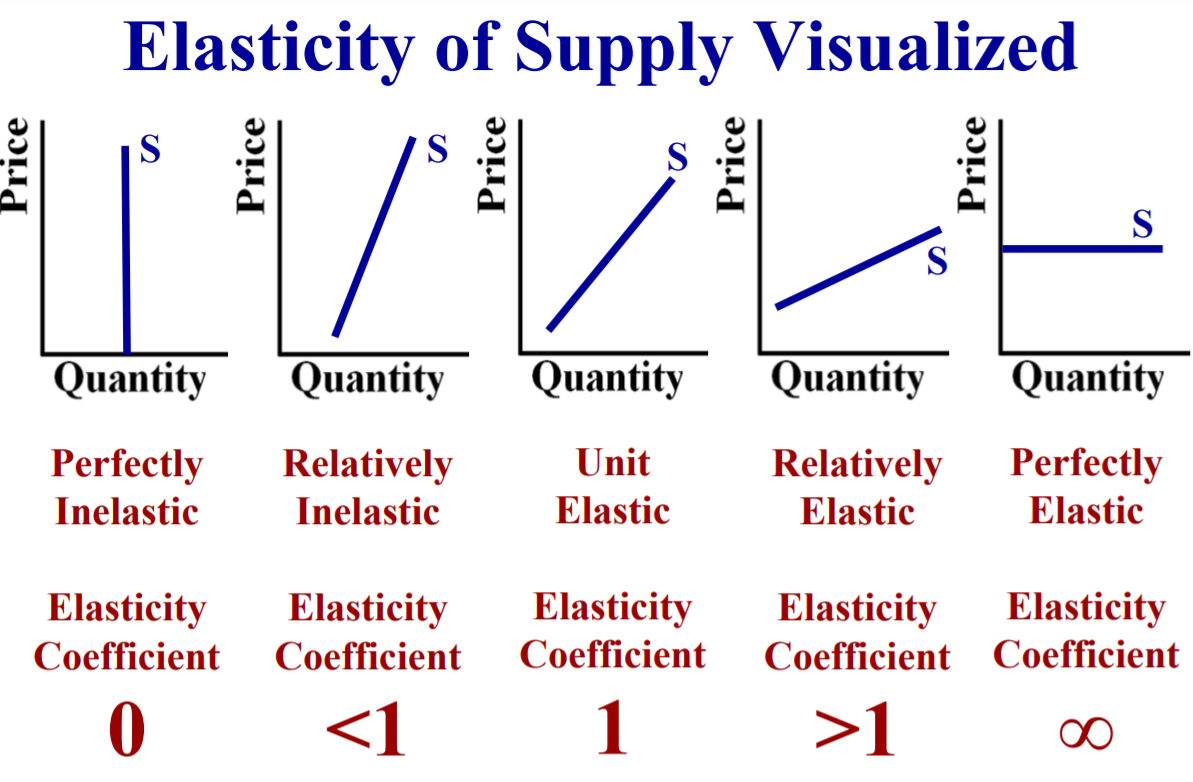

Theory as well as logic raises significant questions about this maximizing assumption. The notion held by the followers of staples theory that tobacco supply increased with the price of tobacco is a straightforward extrapolation of a textbook supply diagram. The standard textbook supply diagram shows that higher prices led to greater quantity and lower prices led to reduced quantity, or as economists would say, a forward-sloping curve, positively elastic. 4 (See Figure 2.)

Now such an assumption of a forward-sloping supply curve would likely be justified if planters could readily switch between alternative staples like wheat and tobacco, but not in a monoculture like the 17th-century Chesapeake. If there were many alternative ways of earning income, then planters could move into tobacco when the price rose and move out when the price fell thus generating a standard supply curve. Such a situation might fit 18th-century North Carolina where there was a fairly diversified economy. But when there were few alternative means of earning income (as in 17th-century Virginia) and the sole staple, tobacco, was a labor-intensive crop with labor by far the most significant factor of production, one cannot make such a simple assumption.

More plausible is the minority Rutman view suggesting that planters produced as much as they could all the time regardless of the price of tobacco, an inelastic supply. But what I will argue, contrary to both interpretations, is that in an economy like that of the 17th-century Chesapeake, one should expect that planters responded to higher tobacco prices by decreasing their productivity and demand for land and labor.

I find strong support for such an argument in a vast literature on the nature of labor supply. A very strong case can be made that the supply of labor is universally rather perverse, or what economists call backward-sloping or negatively elastic. To state it another way, much evidence shows that people universally seem to respond to rising wages with reduced labor and responded to falling wages with increased labor.

Following the seminal statistical work of economist Paul Douglas in 1934, every major study of labor supply, Western or non-Western, whether cross-cultural, cross-class, cross-sectional, or longitudinal, has revealed a significant negative elasticity. 5 In the industrial West labor supply fell as real wages steadily rose, with reductions in labor supply taken in the form of fewer hours of labor per day, fewer days per week, a younger age at retirement, more holidays and longer vacations, and an older age of entry into the work force, again all while real wages were steadily rising.

Similar evidence has also emerged in the last twenty years from experimental and field studies of American farmers, Third World peasants, and business corporations alike. 6 The Western farm and firm are ubiquitously pervaded by what economists call “organizational slack” which only tightens up during recessions or under the pressure of cost-price squeezes, promptly to return again with prosperity and the removal of pressure. 7

Such findings should make us pause in too easily presuming 17th-century Virginians to be industrious maximizers. But rigorous statistical analysis of the extant empirical evidence from the 17th-century Chesapeake leaves no doubt that such presumptions are positively erroneous.

As a result of the work of numerous scholars of colonial Maryland and Virginia, the seventeenth-century Chesapeake is hardly the “statistical ‘dark age'” it was called as recently as 1978. 8 Chesapeake scholars have performed miracles in generating quantifiable data from stingy surviving records. Although we don’t have much individual-level data, we do have enough aggregate-level data, annual times series of tobacco imports, population, prices, acreage, etc., from the late 17th century to analyze three key elements in the colonial Chesapeake economy: the elasticity of tobacco supply, demand for labor, and demand for land.

Now any discussion of multiple regression analysis is going to be necessarily very dry and complex and I’m sure you wouldn’t want me to delve deeply into the subject here, so I’ll be brief. My analysis involved a lot of experimentation with variables and combinations of variables in search of a better fit between predicted and actual data. For example, to test the elasticity of tobacco supply I drew on such data as the annual totals of tobacco imports into England, the size of working population in the Chesapeake, the farm price of tobacco, various measures to gauge the availability of shipping, and proxies of land and labor quality. One of the more innovative aspects of my approach was‑-rather than simply to assume that planters responded to the most immediate prices (as staples theorists often presume)‑-my approach was to experiment with various other ways planters might have reacted to prices: the average price of tobacco over the last so many years, the minimum price over the last so many years. Indeed I found average and minimum prices provided a better fit than current prices.

On tobacco supply, my multiple regression analysis showed that, a fall in the [5-year] average price of tobacco of a tenth of a penny (say from 1.0 to 0.9 pence sterling) led to an increase in tobacco production per tithable of 387 pounds in the late 17th century. So here we have a classic backward-sloping supply curve. The response was totally reversible. A rise in the average price of tobacco of the same tenth of a penny led to an equivalent decrease in tobacco production per tithable.

Figure 3 graphically illustrates the closeness of the match between predicted and actual measures of tobacco productivity. The smooth line is the predicted outcome of my model and the stars are the actual tobacco productivity figures. The model captured 96% of the variance in tobacco productivity. And I would note here that economic historians like Stanley Engerman to whom I have shown my work have been rather impressed at the strength of my models in this supposed statistical dark age. Let me show you how the negative supply elasticity affected tobacco productivity over the late 17th century. For example, the average tobacco hand in 1687 when prices were relatively low produced 1330 pounds more than he did in 1669 when prices were relatively high, a rise in productivity resulting directly from the fall in tobacco prices. 9 On the other hand, the average tobacco hand in 1701 produced 198 pounds less tobacco than he had in 1687, a fall in productivity resulting directly from the rise in tobacco prices during the Peace of Ryswick. 10

Statistical analysis shows a parallel response in the demand for labor and land. Falling tobacco prices led planters to expand production by acquiring more labor and more land, and rising prices reduced the drive to expand.

The superiority of average and minimum prices over current prices further suggests that planters were conservative; they did not respond quickly to changing tobacco prices, but rather averaged in current prices with those of the recent past in making their production decisions. They hedged their bets by basing their decision in part on minimum prices, suggesting safety-first behavior, an unwillingness to gamble that prices would not fall back to such lows again.

These findings turn on its head the view of historians that 17th-century Virginians were industrious maximizers. But how should we understand such behavior? Were seventeenth-century planters simply lazy? Economically backward? Somehow different than later Americans? I think the answer lies in accepting that people then and now simply are not maximizers, so there is no need to suggest that any behavior less than maximizing is somehow perverse. Rather my reading in the literature of cognitive psychologists and other critics of neo-classical economics suggests people do not have some sort of utility function they seek to maximize but rather have standards of living. Pressure on that standard promotes increased effort and risk-taking. The removal of pressure in times of prosperity does not encourage further effort and risk-taking, but creates a condition of satisfaction or well-being that encourages decreased effort and risk-taking. These standards I should note are sticky but not static, tending to creep up in good times and fall back in bad times. Interestingly, I found the roots of these idea in the 17th-century maxim “Necessity is the mother of invention,” so popular among Englishmen on both sides of the Atlantic.

Such a theoretical framework provides a basis for reorienting our understanding of other aspects of the lives of these planters. Thus we can see how the impact of cost-price squeezes in the late seventeenth century forced planters not only to increase tobacco production and demand for labor and land but also to cut back on imports, increase domestic production, diversify their crops, undertake new enterprises, migrate to other colonies or back to England, delay marriage, search for more efficient production and transportation techniques, and, most significantly for the course of American history, shift from white indentured servants to African slaves. 11 12 Unlike tobacco supply elasticity on which they rarely commented, 17th-century Virginians noted regularly how the necessity of low tobacco prices forced them to take on these alternative responses.

Yet the question still remains why the historians of the colonial Chesapeake have completely missed the picture. It is not because these historians have not had available alternative theory, statistical tools, or hard empirical data. Rather Chesapeake scholars seem to suffer from a curious blindspot, a paradigmatic bias that I call the myth of maximizing.

Certainly part of the problem can be written off as American exceptionalism. 13 One can find such exceptionalism prominent among seventeenth-century Virginians themselves who celebrated the miraculous transformation of lazy Englishmen into industrious planters. Perhaps more directly one can trace this exceptionalism to the nationalistic rhetoric of the post-revolutionary era. In particular the idea that the American character was shaped by the pull of abundant Western land was an idea echoed by Franklin, Crèvecoeur, Jefferson, Tocqueville, Emerson, Lincoln, Whitman, and hundreds of other early American thinkers. 14 15 By the mid-nineteenth century, the belief that the American yeoman was “a different creature altogether” from the European peasant had come to dominate American thought. 16 The American was by definition industrious, whether pushed by the duty of taming a frontier, the irrepressible competition of fellow Americans, and a Protestant work ethic; or pulled by freedom, opportunity, and abundance. These ideas, as Henry Nash Smith well noted, received their “classic statement” in Turner’s frontier thesis that has colored so much of twentieth-century historiography. 17

But clearly American exceptionalism cannot be the sole explanation for this blindspot since historians are not averse to challenging American exceptionalism. All of the major shifts in American historiography‑-from Whig to Progressive to counter-Progressive to neo-Progressive‑-have challenged some aspect of the American exceptionalism of the preceding generation of historians.

Rather I believe the myth stems as well from two pervasive ideas in the social sciences. One, of course, is the idea of utility maximization so central to neo-classical economics that more often than not gets translated as profit maximization.

The other key idea is the Marxian-Weberian idea of a transition to capitalism. Central to Marx’s thinking was the idea of the irrepressible force of capitalism, a Darwinian struggle that relentlessly pushes men under the capitalist mode of production, regardless of the traditional or modern mindset of the individuals or communities involved. To this Max Weber added the idea of a Protestant work ethic which could achieve an equally effective if more fragile push, enough to get the whole process started. But soon, for Weber as for Marx, capitalism became its own driving force, “an immense cosmos into which the individual is born,” governed by the law of maximization.

Whether historians have been more influenced by American exceptionalism, Turner’s frontier thesis, Marxian-Weberian theory, or neo-classical economic theory, all have worked hand-in-hand to reinforce the myth of maximizing. The power of this myth readily explains why historians have treated 17th-century Virginians as maximizers despite all the problems of logic, theory, and empirical evidence. But these problems should suggest that it is high time we re-examine the implicit assumptions that we bring to our work about the nature of economic motivation and behavior, and recognize how those assumptions distort our ability to understand not only early Americans but also other peoples in the past and present and, indeed, ourselves today.

Notes:

- Darrett B. Rutman and Anita H. Rutman, A Place in Time: Middlesex County, Virginia, 1650-1750 (New York: Norton, 1984) 42-3, 75, 183-4; Charles Wetherell, “‘Boom and Bust’ in the Colonial Chesapeake Economy,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 15 (1984): 185-210, esp. 197, 204, 208-9; Anita H. Rutman, “Still Planting the Seeds of Hope: The Recent Literature of the Early Chesapeake Region,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 95 (1987): 5-7; Darrett B. Rutman, Small Worlds, Large Questions: Explorations in Early American Social History, 1600-1850 (Charlottesville: UP of Virginia, 1994) 10-1. ↩

- Thomas J. Wertenbaker, The Planters of Colonial Virginia (1922; New York: Russell, 1958) 63-4; Lewis Cecil Gray, History of Agriculture in the Southern United States to 1860, 2 vols. (1933; Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1958) 1: 218-9; Melvin Herndon, Tobacco in Colonial Virginia: ‘The Sovereign Remedy’ (Williamsburg, VA; Virginia 350th Anniversary Celebration Corporation, 1957) 11; John C. Rainbolt, From Prescription To Persuasion: Manipulation of Eighteenth [Seventeenth] Century Virginia Economy (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat, 1974) 56; Edmund S. Morgan, “The First American Boom: Virginia 1618 to 1630,” William and Mary Quarterly 3rd ser. 28 (1971): 177‑8; Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: Norton, 1975) 109-10, 110n12, 142, 142-3n33, 302; Anderson and Thomas 377, 382-5; Menard, “Tobacco Industry” 115, 145, 153; Paul G. E. Clemens, The Atlantic Economy and Colonial Maryland’s Eastern Shore: From Tobacco to Grain (Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1980) 35, 111-2, 150-1; Gloria L. Main, Tobacco Colony: Life in Early Maryland, 1650‑1720 (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1982) 38, 40; Darrett B. Rutman and Anita H. Rutman, A Place in Time: Explicatus (New York: W. W. Norton, 1984) 9-24; Russell R. Menard, Economy and Society in Early Colonial Maryland (New York: Garland, 1985) 202-5, 239-42, 401n92, 459-62; Lorena S. Walsh, “Plantation Management in the Chesapeake, 1620-1820,” Journal of Economic History 49 (1989): 394-5. ↩

- Rutman and Rutman, Middlesex 42‑3. ↩

- https://www.tamdistrict.org/cms/lib/CA01000875/Centricity/Domain/1076/Presentation_3_Elasticity_of_Demand_and_Supply.pdf ↩

- This suggests an increase of one per cent in real wages decreases the quantity of labor supplied by one-tenth to one-third per cent, and a decrease of one per cent in real wages increases the quantity of labor supplied by one-tenth to one-third per cent. Cf. Douglas 313. Such a range of elasticity also challenges also the notion of a target income (i.e., an elasticity of ‑1.0) since the actual supply is far closer to an inelastic response. On the elasticity of labor supply in the United States and Western Europe, see George F. Break, “Income Taxes, Wage Rates, and the Incentive to Supply Labor Services,” National Tax Journal 6 (1953): 333-52; Clarence D. Long, The Labor Force under Changing Income and Employment (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1958); Frank Gilbert and Ralph W. Pfouts, “A Theory of the Responsiveness of Hours of Work to Changes in Wage Rates,” Review of Economics and Statistics 40 (1958): 116‑21; Harold L. Wilensky, “The Uneven Distribution of Leisure: The Impact of Economic Growth on ‘Free Time,'” Social Problems 9 (1961): 32-3; T. Aldrich Finegan, “The Backward-Sloping Supply Curve,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 15 (1962): 230-4; M. S. Feldstein, “Estimating the Supply Curve of Working Hours,” Oxford Economics Papers 20 (1968): 74‑80; William G. Bowen and T. Aldrich Finegan, The Economics of Labor Force Participation (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1969); Sherwin Rosen, “On the Interindustry Wage and Hours Structure,” Journal of Political Economy 77 (1969): 249-73; Albert Rees, “An Overview of the Labor-Supply Results,” Journal of Human Resources 9 (1974): 158-80; Edward Kalachek, Wesley Mellow, and Frederic Raines, “The Male Labor Supply Function Reconsidered,” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 31 (1978): 356-67; Fred Best and James D. Wright, “Effects of Work Scheduling on Time-Income Tradeoffs,” Social Forces 57 (1978): 136-53. For the most complete overview of the Western literature, see John Pencavel, “Labor Supply of Men: A Survey,” Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. I, eds. Orley Ashenfelter and Richard Layard (Amsterdam: North, 1986) 3-102. On cross-cultural measures of the elasticity of labor supply, see Charles P. Kindleberger, Economic Development, 2nd ed. (New York: McGraw, 1965) 6; Gordon C. Winston, “An International Comparison of Income and Hours of Work,” Review of Economics and Statistics 48 (1966): 28-39; Howard N. Barnum and Lyn Squire, A Model of an Agricultural Household: Theory and Evidence (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1979) 9-12, 15-6, 81-2; Julian L. Simon, The Economics of Population Growth (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1977) 58-61, 134; Mark R. Rosenzweig, “Neoclassical Theory and the Optimizing Peasant: An Econometric Analysis of Market Family Labor Supply in a Developing Country,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 94 (1980): 49-54; Inderjit Singh, Lyn Squire, and John Strauss, eds., Agricultural Household Models: Extensions, Applications, and Policy (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1986) 25-7. ↩

- On farming, see Gavin Wright and Howard Kunreuther, “Cotton, Corn and Risk in the Nineteenth Century,” Journal of Economic History 35 (1975): 526-51; Richard H. Day and Inderjit Singh, Economic Development as an Adaptive Process: The Green Revolution in the Indian Punjab (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1977) 19-39; James A. Roumasset et al., eds., Risk, Uncertainty, and Agricultural Development (New York: Agricultural Development Council, 1979); Paul J. H. Schoemaker, Experiments on Decisions under Risk: The Expected Utility Hypothesis (Boston: Kluwer, 1980); Lola L. Lopes, “Between Hope and Fear: The Psychology of Risk,” Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 20 (1987): 287‑8; Harriet Friedmann, “World Market, State, and Family Farm: Social Bases of Household Production in the Era of Wage Labor,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 20 (1978): 565-6; Alice Saltzman, “Chayanov’s Theory of Peasant Economy Applied Cross-Culturally: Family Life Cycle Influences on Economic Differentiation and Economic Strategy,” diss., U of California, Irvine, 1985, 125-220; Alan Collins, Wesley N. Musser, and Robert Mason, “Prospect Theory and Risk Preference of Oregon Seed Producers,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 73 (1991): 429‑35. On insurance, see Howard Kunreuther, et al., Disaster Insurance Protection: Public Policy Lessons (New York: Wiley, 1978); Schoemaker, Experiments. On the corporate firm, see Kenneth E. Boulding, The Organizational Revolution: A Study in the Ethics of Economic Organization (New York: Harper, 1953) 137-8; James G. March and Herbert A. Simon, Organizations (New York: Wiley, 1958) 172-86; Michel Crozier, The Bureaucratic Phenomenon (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1964) 195-8; Harvey Leibenstein, “Organizational or Frictional Equilibria, X-Efficiency, and the Rate of Innovation,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 83 (1969): 621; Robert D. Cuff, “American Historians and the ‘Organizational Factor,” Canadian Review of American Studies 4 (1973): 26-7; E. H. Bowman, “Risk Seeking by Troubled Firms,” Sloan Manangement Review 23 (1982): 33‑42; Jitendra V. Singh, “Performance, Slack, and Risk Taking in Organizational Decision Making,” Academy of Management Journal 29 (1986): 562-85; Stanley Kaish, “Behavioral Economics in the Theory of the Business Cycle,” Handbook of Behavioral Economics, Vol. B: Behavioral Macroeconomics, eds. Benjamin Gilad and Stanley Kaish (Greenwich, CT: JAI, 1986) 40; Avi Fiegenbaum and Howard Thomas, “Attitudes toward Risk and the Risk-Return Paradox: Prospect Theory Explanations,” Academy of Management Journal 31 (1988): 85-106; Neil Fligstein, The Transformation of Corporate Control (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1990) 3-23, 300. On innovative and entrepreneurial behavior in general, see Reuven Brenner, History‑-The Human Gamble (Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1983) 88; Mary Douglas, Risk Acceptability According to the Social Sciences (New York: Sage, 1985) 73-82. ↩

- Wesley Clair Mitchell, Business Cycles and Their Causes (1941; Berkeley: U of California P, 1960) 16-8, 33-4, 38-9; March and Simon 126; Richard M. Cyert and James G. March, A Behavioral Theory of the Firm (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice, 1963) 10, 36-8; Harvey Leibenstein, Beyond Economic Man: A New Foundation for Microeconomics (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1976) 392-415; John Kendrick, Understanding Productivity: An Introduction to the Dynamics of Productivity Change (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1977) 67; Roger Frantz and Fred Galloway, “A Theory of Multidimensional Effort Decisions,” Journal of Behavioral Economics 14 (1985): 78. ↩

- Terry L. Anderson and Robert Paul Thomas, “Economic Growth in the Seventeenth-Century Chesapeake,” Explorations in Economic History 15 (1978): 368. ↩

- 1256 pounds due to fall in PA5 from 1.21 to 0.883 pence and 74 pounds due to fall in PMIN4 from 0.90 to 0.80 pence. Tobacco productivity actually rose only 445 pounds per tithable from 866 to 1311 pounds, primarily due to the influence of the downward time trend which reduced tobacco productivity by 677 pounds per tithable over the period. ↩

- 161 pounds due to rise in PA5 from 0.883 to 0.925 pence and 37 pounds due to rise in PMIN4 from 0.80 to 0.85 pence. Actual productivity fell by 450 pounds per tithable from 1311 to 861 pounds, due again primarily to the influence of the downward time trend which reduced tobacco productivity by 527 pounds per tithable over the period. ↩

- Gloria L. Main, Tobacco Colony: Life in Early Maryland, 1650-1720 (Princeton: Princeton UP, 1982) 24, 48-96. Cf. Gloria L. Main, “Maryland and the Chesapeake Economy, 1670-1720,” Law, Society, and Politics in Early Maryland, eds. Aubrey C. Land, Lois Green Carr, and Edward C. Papenfuse (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1977) 134-52; Main, Tobacco Colony 5-8, 16, 18, 58-9, 69-71, 253, 274. ↩

- Darrett B. Rutman, The Morning of America, 1603‑1789 (Boston: Houghton, 1971) 77; K. G. Davies, The North Atlantic in the Seventeenth Century (Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1974) 152; Carville V. Earle, The Evolution of a Tidewater Settlement System: All Hallow’s Parish, Maryland, 1650-1783 (Chicago: U of Chicago, Dept. of Geography, 1975) 14; Paul G. E. Clemens, The Atlantic Economy and Colonial Maryland’ s Eastern Shore: From Tobacco to Grain (Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1980) 82, 214-5; Rutman and Rutman, Middlesex 184; Warren M. Billings, John E. Selby, and Thad W. Tate, Colonial Virginia: A History (White Plains, NY: KTO, 1986) 124; Allan Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800 (Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1986) 49; McCusker and Menard 127. ↩

- For the recent literature on American exceptionalism, see Byron E. Shafer, Is American Different?: A New Look at American Exceptionalism (Oxford: Clarendon, 1991); Joyce Appleby, “Recovering America’s Historic Diversity: Beyond Exceptionalism,” Journal of American History 79 (1992): 419-31; Michael Kammen, “The Problem of American Exceptionalism: A Reconsideration,” American Quarterly 45 (1993): 1-43; Jack P. Greene, The Intellectual Construction of America: Exceptionalism and Identity from 1492 to 1800 (Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 1993); David M. Wrobel, The End of American Exceptionalism: Frontier Anxiety from the Old West to the New Deal (Lawrence: UP of Kansas, 1993). ↩

- The classic analysis of the history of this idea is Henry Nash Smith, Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol and Myth (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1950). ↩

- Crèvecoeur 69-70, 84. ↩

- H. Smith, Virgin Land 135. ↩

- H. Smith, Virgin Land 3. ↩