Scholars have long lamented how difficult it is to pin down color terms in classical Latin.[1] But of all the classical colors no two have probably caused more confusion than ferrugo and ferrugineus.[2] Just to take one example, ferrugineus in Plautus has been translated as everything from cerulean to dark violet to dark brown to “rust-coloured” to dark gray to “dark-coloured” to rostigbraun to noir.[3] And this is not to embarass scholars of Plautus. Scholars of Lucretius, Catullus, Virgil and Ovid have all been in the same (Charon’s) boat!

Jacques André, the respected authority on Latin color terms, lists ferrugo/ferrugineus under three separate chromatic headings, “rouge”, “noir” and “vert” without attempting to make sense of how ferrugo/ferrugineus could be this strange combination of colors.[4] The Oxford Latin Dictionary defines ferrugo as “the term for shades of colour, apparently ranging from a reddish-purple to near-black” and ferrugineus as “having a dark purplish colour, somber-coloured”.[5]

And how the Romans could have derived such a range of colors from ferrugo boggles the mind, because scholars all agree that ferrugo was quite simply iron rust and, when we think of iron rust today, we think of a fairly uncomplicated red-brown-orange color we actually call in English by the name “rust”. (See Fig. 1)

Fig. 1 Rusty chain

The number of extant examples of these two words is not large. If we restrict ourselves to authors writing before 200 CE, there are altogether only 16 extant instances of ferrugo (Catullus – 1, Virgil – 3, Ovid – 5, Tibullus – 1, Culex – 1, Valerius Flaccus – 1, Laus Pisonis – 1, and Pliny the Elder – 3) and 11 instances of ferrugineus (Plautus – 2, Lucretius – 1, Virgil – 2, Statius – 2, Columella – 1, and Pliny the Elder – 3).[6] Unfortunately, none of these writers by themselves or combined together really provides a solid explanation of the meaning of ferrugo and ferrugineus. It is only by looking beyond these writers, drawing upon a wide-ranging body of ancient and modern knowledge about ironworking, dyestuffs, plants, and other subjects related to the context in which ferrugo and ferrugineus were used, and going beyond traditional assumptions that we can start to understand what they meant by these two terms.

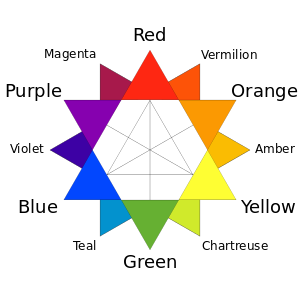

Although whenever you are dealing with ancient colors nothing can be perfectly resolved, this paper proposes that most of the confusion can be resolved if we accept that Roman writers did not use ferrugo to refer to the familiar red-brown-orange substance which is associated with the color “rust” today, a substance that goes by the modern scientific name of hydrated Iron (III) oxide with chemical formula Fe2O3·nH2O. Rather, by ferrugo, they meant the black substance that goes by the modern scientific name Iron (II, III) oxide with chemical formula Fe3O4 which forms on iron heated in a charcoal-fueled forge. (See Fig. 2.) Furthermore, ferrugineus did not mean the normal black color of Iron (II, III) oxide, as might be expected, but rather the dark blue hue that emerges from a very thin layer of this oxide on tempered steel (the blue corresponding to 590ºF or 310ºC as seen in Fig. 3), synonymous with the color that ancient Romans referred to more commonly as caeruleus.

Fig. 2 Iron (II, III) oxide Fe3O4

Fig. 3 Tempering Colors of Steel

Ferrugo versus Robigo

Although modern translators and commentators disagree over what color ferrugo represents, they recognize that the color must have been originally rooted in some substance that Romans believed had that color, a substance that the Romans called ferrugo. The general assumption today is that, by ferrugo, the Romans meant what we would call today “iron rust”.[7] Scholars further support this understanding by noting the similarity of ferrugo to other “rust” words like robigo and aerugo. The suggestion is that all these “rust” words are related. Indeed most commentators treat robigo as a generic word for rust that might be applied to iron, copper/bronze or any metal. In this framework, ferrugo is simply a shorthand form of robigo ferri (“rust of iron”) and aerugo a shorthand form of robigo aeris (“rust of copper/bronze”).[8]

The ancients, however, made no such assumptions about ferrugo. Indeed, it was only in the 16th century that the idea that ferrugo = “iron rust” seems to have appeared and then quickly achieved the status of a truism. One cannot find a single classical or medieval reference equating ferrugo with robigo ferri. Medieval writers instead defined ferrugo either as ferri scuriae (“iron slag”), ferri rasura (“shaving of iron”), or ferrari rasura (“blacksmith’s shaving”). Simon of Genoa as late as the 13th century wrote that ferrugo, scoria of iron and cacaferri (“dung of iron”) were all the same thing; they were the lumps that ironsmiths removed from their furnaces. But none of these medieval writers ever defined ferrugo as a form of robigo.[9]

How different would be the 16th century when Antonio Telesio (1482-1534) in his Libellus de Coloribus (Booklet on Colors) defined ferrugineus simply as the color of “iron that has rusted for a long time” (ferrum longo situ rubiginosum).[10] And Ambrogio Calepino, compiler of the best-selling Latin dictionary of the 16th century, wrote that ferrugo “is properly called rust of iron just as aerugo of copper” (rubigo ferri proprie dicitur, sicut aerugo, aeris).[11] And Georg Agricola, the renowned father of mineralogy, in his Interpretatio (1546), defined ferrugo as the equivalent of the German Rost.[12] Robert Estienne did the same for French, equating ferrugo with Rouillure, ou Rouillure de fer.[13]

For their part, the Romans never used ferrugo for iron rust because they had a perfectly good word for iron rust. It was robigo.

Scholars have given some attention to the numerous Latin nouns of feminine gender like ferrugo, aerugo, and robigo, ending with the suffixes –āgō, īgō, or ūgō. Alfred Ernout, noting the frequent appearance of these suffixes in the names of particular diseases or defects and the names of various plants, suggested that they served to designate some alteration or change of state. More recently Georges-Jean Pinault has stated that the Indo-European roots of the suffixes –āgō, īgō, or ūgō implied some kind of action. He shows, for example, how robigo derived from an Indo-European word meaning essentially “that which reddened”.[14]

As Ernout and Pinault and all other philologists have asserted, the only feasible referent for ferrugo is ferrum (“iron”). We might conclude, following Ernout, that ferrugo represented some changed state of iron. Or, following Pinault, that ferrugo implied some kind of action involving iron. From such an understanding of ferrugo, it is easy to see why commentators past and present would interpret ferrugo as iron rust. Clearly iron rust is the most obvious changed state or action that most readily comes to mind when we speak of iron. But that is not what the Romans meant by ferrugo.

Before robigo was ever applied to metals, it was applied to wheat and other grains. Every 25th of April Romans celebrated Robigalia in order to assure their grain protection from the blight/mildew/smut/mold which they called robigo and which even today we call “rust.”[15] Today we know that the plant diseases called rust are caused by numerous species of pathogenic fungi that can affect the leaves, stems, fruits, and seeds of a variety of plants. And many of them, like leaf rust (e.g., Puccinia triticinia) (see Fig. 4), do indeed cause the plant to turn a reddish-brown color so we can see perhaps how Romans might have called the fungus that attacked their wheat crops by the name of robigo. Undoubtedly because of the similarity in color between the reddish-brown of wheat blight and the reddish-brown of iron rust, as well as the connotations of disease and a change of state, the term robigo was extended to what we call iron rust.[16]

Fig. 4 Close-up of wheat leaf rust (Puccinia triticinia) on wheat

Apart from a couple of references in Pliny (discussed below), the only specific metal mentioned with robigo was always iron, and always in the sense of something attacking, corroding, fouling, or corrupting the iron. The earliest reference to robigo in Latin literature gives a quite clear description of the Roman understanding of robigo. Plautus in his comedy Rudens (“The Rope”), believed to have been written around 211 BCE, describes a situation in which a spit had turned into solid rust. If there was just a little rust on the spit, polishing could remove it and make the spit shiny again. But polishing made the spit redder and more slender because all that kept coming off was rust (Pl. Rud. 5.2.12-15). Similarly, Virgil in the Georgics wrote about salty rust attacking iron (Verg. G. 2.220) and Ovid in Ex Ponto about rust gnawing away at iron (Ov. Pont. 1.1.71-72). Indeed, so prevalent was this sense of robigo that in the early seventh century CE, Isidore of Seville in his Etymologies asserted that “Rust (robigo) is a corroding (rodere) flaw of iron, or of crops, as if the word were rodigo, with one letter changed.”[17]

Generic rust of metals?

One can easily see from just these examples that Romans applied the term robigo much as we would apply the term “iron rust” or just plain “rust” today. There is little support, however, for the argument that Romans saw robigo as a generic rust of metals.[18]

The one exception is Pliny the Elder who in a few instances writes of a robigo of copper/bronze, something no other Roman does. But Pliny had something very specific in mind when he applied robigo to copper/bronze, and it was not a generic rust of metals. Robigo for Pliny was always first and foremost reddish. Pliny went so far as to describe a salt of a yellow or reddish color (crocei coloris aut rufi) as “a kind of rust of salt” (veluti rubigo salis) (Plin. Nat. 31.42).[19]

When speaking of robigo and iron, Pliny is pretty much in line with the general understanding of robigo as a reddish substance that attacked iron. For example, in one passage he states

obstitit eadem naturae benignitas exigentis ab ferro ipso poenas robigine eademque providentia nihil in rebus mortalius facientis quam quod esset infestissimum mortalitati. (Plin. Nat. 34.55)

Nature, in conformity with her usual benevolence, has limited the power of iron, by inflicting upon it the punishment of rust; and has thus displayed her usual foresight in rendering nothing in existence more perishable, than the substance which brings the greatest dangers upon perishable mortality.

But Pliny also seemed to believe that one can find this same robigo on copper/bronze. For instance, Pliny observed that robigo had the same medicinal virtue whether prepared from copper/bronze or iron. In recounting the story of how Achilles cured Telephus’ uncurable wound by shaving the robigo off the sword into the wound, Pliny stated that it did not matter whether it was a bronze or an iron sword. Although he acknowledged that robigo ferri (literally “rust of iron”) obtained from old iron nails was typically used in his own time for this remedy, he asserted that robigo from copper worked just as well as robigo from iron (Plin. Nat. 34.60).

In his thinking about robigo, Pliny may have had in mind the word ἰός (ios) which Greek writers did indeed use in the sense of a rust that attacks both iron and copper/bronze. For example, Plato wrote that everything has its congenital evil and disease. Iron and bronze have their ios just like grain has its mildew, wood its rot, and the eyes their opthalmia (Plat. Rep. 609a).[20] Indeed, as Sappho and others had long noted, the only metal immune from ios was gold.[21] Pliny makes a similar statement to that of Sappho:

[aurum] super ceterea non robigo ulla, non aerugo, nonaliud ex ipso, quod consumat bonitatem minative pondus. (Plin. Nat. 33.20)And then, more than anything else, [gold] is subject to no robigo, no aerugo, no emanation whatever from it, either to alter its quality or to lessen its weight.

But even here Pliny did not seem to think of robigo as a generic ios. Rather he saw robigo as a particular form of ios, just as he saw aerugo as a particular form of ios. It is interesting that neither here nor anywhere else does he suggest that ferrugo was a form of ios. One can see this especially in the way Pliny deals with the medicinal virtues of robigo and aerugo.

Pliny’s description of the medicinal virtues of robigo (Plin. Nat. 34.60) and Dioscorides’ highly similar account of the medicinal virtues of ἰός σιδήρου (ios siderou, siderou = “of iron”) in his De materia medica (Dsc. 5.80) leave no doubt that they were writing about the same substance. In both, the substance is astringent; cures loss of hair, granulations/scabs of the eyelid, and whitlows; stops female discharge; is useful for venereal warts; and alleviates gout. They indeed are so similar that it very much appears that either one was copying the other or else they were both drawing on a common third source. Max Wellmann argued convincingly back in the late 19th century that it was a third source and, more often than not, that source was Sextius Niger who wrote a treatise also called De materia medica around 10-40 CE.[22] Thus we can conclude that Pliny here is translating the Greek ἰός σιδήρου as robigo. In a similar way, we can demonstrate that Pliny also translated Sextius Niger’s ἰός ξυστός (ios xustos) as aerugo because the methods of preparing this substance are highly similar in both Pliny (Plin. Nat. 34.43) and Dioscorides (Dsc. 5.79). Overall it seems that Pliny considered robigo as the ios of iron and aerugo as the ios of copper/bronze.

Perhaps the only way to make sense of Pliny’s statements on robigo is that he believed it was a “disease” that affected both iron and copper/bronze, but copper/bronze was more impervious to the disease than iron.[23] That would explain why, when speaking of copper/bronze, he uses the rather mild verb trahere (“to take on, assume, acquire, get”) in contrast to the verb infestare (“to attack, destroy, injure, impair”) when speaking of iron (Plin. Nat. 7.24, 34.37, 34.58). This distinction might also explain why Pliny several times mentions robigo in the context of iron instead of more generally both iron and copper/bronze (Plin. Nat. 17.5, 31.22, 34.56). For example, on Aristonidas’ statue made of copper and iron, it was only the robigo of iron that would appear through the shiny copper, not the other way around (Plin. Nat. 34.55).

That Pliny would treat copper and iron differently when it comes to “rust” would not be too surprising to us today. We know that copper simply does not rust like iron. Copper/bronze acquires a dull brownish coating of cuprous and cupric oxides when exposed to air over time. One can imagine that Pliny might see this coating as akin to robigo due to the color change even if we would not today. But the Romans certainly knew, as we do today, that such rust was not as much a problem when it came to copper as it was for iron. That is why, as Pliny states, the ancients built their monuments and tablets on which are engraved public enactments out of copper/bronze and not iron. Obviously Pliny’s rust of copper was not such a bad problem that pronouncements could not be read decades later. Similarly “Indian head pennies” from the 19th century, as brown as they might be, still look as good as Lincoln head pennies from the 1990’s even if nothing special is done to maintain them.[24]

Pliny & Ferrugo

So what did Pliny think ferrugo was? Pliny barely mentions ferrugo in Naturalis Historia. In contrast to his thirty references to robigo/rubigo (including thirteen which specifically link robigo with ferrum), he only uses the term ferrugo three times. But each of these three instances leads one to believe that Pliny conceived of ferrugo as a rather amorphous, powdery black substance quite distinct from reddish-brown robigo. When it came to ferrugo, Pliny did not see red. He saw black.

Pliny provides an excellent clue to the nature of ferrugo in his very precise description of the pine nut (pineis nucibus).

grandissimus pineis nucibus altissimeque suspensus. intus exiles nucleos lacunatis includit toris, vestitos alia ferruginis tunica, mira naturae cura molliter semina conlocandi. (Plin. Nat. 15.10)

The largest [fruit] and the one that hangs at the greatest height is the pine-nut. It contains within small kernels, enclosed in hollowed-out beds and covered by another coat of ferrugo; Nature thus manifesting a marvelous degree of care in providing its seeds with a soft receptacle.

There is little doubt that Pliny was describing the tree that goes by the scientific name of Pinus pinea, commonly called in English the “stone pine”, a tree that has been cultivated in the Mediterranean basin for over 6,000 years and whose nuts were regularly consumed by Romans in Pliny’s time.[25] (See Fig. 5.)

Fig. 5 Stone-pine nuts

As for what Pliny meant by “another coat of ferrugo“, one might note that he has a similar phrase in describing the acorn of which he says some have beneath the shell a rough coat of robigo (tunica robigine scabra) while in others a white flesh immediately presents itself (Plin. Nat. 16.11). While translators have typically rendered ferrugo and robigo here as color terms, Pliny was likely saying these “coats” were very much like the substance he called ferrugo and robigo, certainly a far stronger statement than a mere color term. By the rough coat of robigo Pliny must have been referring to acorns that have, beneath the outer shell, a thin brown corky layer that sometimes clings to the light-colored flesh.[26] By ferrugo, Pliny was referring to the black powdery substance that covers the hard shell of the stone-pine nuts and rubs off quite easily.[27]

Putting two and two together, if ferrugo represented a changed form of iron and was a powdery black substance, it is quite clear that what Pliny was referring to was not the reddish-brown substance that we call “iron rust” and goes by the modern scientific name of hydrated Iron (III) oxide with chemical formula Fe2O3·nH2O. Rather his referent must have been to the black substance that forms on iron or steel when heated in a forge fueled by charcoal which goes by the modern scientific name of Iron (II, III) oxide, with chemical formula Fe3O4. In mineral form it is known most commonly as magnetite. It is this black oxide that is most likely behind the fact that iron is known as “the black metal” in so many apparently unrelated cultures, including Chinese tie, Japanese kurogane, Russian chernaya metallurgiya, and English “black metal” (from which we get “blacksmith”).[28]

The two other references to ferrugo in Pliny also lead us to believe that he conceived of ferrugo as the black Iron (II, III) oxide formed on iron heated in a charcoal forge.

sudor virgae corni arboris, lamna candente ferrea exceptus non contingente ligno, inlitaque inde ferrugo incipientes lichenas sanat. (Plin. Nat. 23.71)

The juices which exude from the branches of the cornel are received on a plate of red-hot iron without it touching the wood; the ferrugo of which is applied for the cure of incipient lichens.[29]

If the iron plate was made red hot by heating in a charcoal forge, there would already have been a fairly thick layer of Iron (II, III) oxide on the surface when it was taken out of the forge.[30] As for the effect of the cornel juice, anything organic in the juice would have eventually carbonized into amorphous black elemental carbon on the red-hot plate.[31] One imagines that the Romans might not have distinguished between amorphous Iron (II, III) oxide and carbon all mixed together.

Pliny’s third example of ferrugo also supports the Iron (II, III) oxide hypothesis.

antiqui axibus vehiculorum perunguendis maxime ad faciliorem circumactum rotarum utebantur, unde nomen, sic quoque utili medicina cum illa ferrugine rotarum ad sedis vitia virilitatisque et per se axungia. (Plin. Nat. 28.34)

The ancients used to employ hogs’ lard in particular for greasing the axles of their vehicles, that the wheels might revolve the more easily, and to this, in fact, it owes its name of “axungia.” When hogs’ lard has been used for this purpose, incorporated as it is with the ferrugo of the wheels, it is remarkably useful as an application for diseases of the rectum and of the generative organs.

This kind of animal fat got its name axungia (“axle grease” = axis “axle” + ungere “to grease”) from its main use as axle grease.[32] The iron wheel fittings found preserved in a hoard at the bottom of Rhine River near Neupotz dated to the 3rd century CE (see Fig. 6) show very clearly how the Romans constructed the wheels described by Pliny. The hubs of wooden Roman wheels were typically lined with iron hub rings and wooden axles were reinforced with iron bushings that were designed to be placed inside of the wheels. Thus, when the wheel turned, it would have meant metal on metal and, with sufficient axle grease, friction would have been much less than wood on wood or metal on wood.[33]

Fig. 6 Neupotz

It is quite likely that the blacksmiths realized that the black oxide coating on the surface of the iron bushing and ring had some benefits that might well be worth preserving. There are modern companies that specialize in “black oxide coating” of small items like machine parts (bearings, shafts, springs, etc.). Benefits include strong adhesion (far superior to paint), good lubrication characteristics, and corrosion protection.[34] Lubrication engineers report that the magnetite film on steel parts is “beneficial in reducing friction and wear by reducing metal to metal contact during boundary lubrication.” Mild adhesive wear eventually leads to fragments of Iron (II, III) oxide mixing with the oil or grease, as one imagines would have happened with axungia, thus yielding the axungia that Pliny recommended as a medical remedy.[35]

Ferrugineus Sapor

The connection of ferrugo with the black oxide that forms on red-hot iron is also suggested by Pliny’s mention of a certain ferrugineus taste in his famous description of the Tungri waters.

Tungri civitas Galliae fontem habet insignem plurimis bullis stillantem, ferruginei saporis, quod ipsum non nisi in fine potus intellegitur. purgat hic corpora, tertianas febres discutit, calculorum vitia. eadem aqua igne admoto turbida fit ac postremo rubescit. (Plin. Nat. 31.4)

The state of the Tungri, in Gaul, has a spring of great renown, which sparkles as it bursts forth with bubbles innumerable, and has a certain ferrugineus taste, only to be perceived after it has been drunk. This water is strongly purgative, is curative of tertian fevers, and disperses urinary calculi: upon the application of fire it assumes a turbid appearance, and finally turns red.

Most scholars assume that the term ferrugineus here simply represents the adjectival form of the noun ferrugo, describing some quality of ferrugo, and thus the Tungri spring water had an aftertaste of ferrugo.

Pliny was seemingly here referring to the taste of the water in which blacksmiths quenched their red-hot iron/steel, water typically called “forge water”, “blacksmith’s water”, or “smithy water” in English.[36] A layer of Iron (II, III) oxide forms as iron becomes red hot in the forge. But when the blacksmith plunges the red-hot iron in water, the iron cools quickly and the shock causes some of the black oxide to break apart and fall off into the water. Somewhere in this process of quenching, the forge water seemingly acquired a taste that Pliny associated with ferrugo.

By the time Pliny was writing his encyclopedia, forge water had become a mainstay among writers on medical subjects, including Celsus, Scribonius Largus, and Dioscorides (Dsc. 5.80). Celsus said the idea originated from the observation that blacksmiths’ animals had small spleens (Cels. 4.16). Scribonius says he got the idea from knowledge of a particular hot water spring in Tuscany some fifty miles away from Rome. Scribonius referred to these waters as ferratae but he said they were called vesicariae because they amazingly cured bladder damage.[37] It is not clear what Scribonius meant by calling these waters ferratae, an adjective almost exclusively applied to objects like iron-rimmed wheels and iron-clad armor, weapons, and tools as meaning “furnished, covered, or shod with iron”.[38] Seneca in his Naturales quaestiones also identified a class of natural mineral waters as ferratas for which he claimed the taste showed the quality.[39]

Unfortunately, no classical writer, including Pliny, ever explicitly described the taste of forge water. Pliny does mention forge water (ferro candente potus) saying it was good for many diseases, especially dysentery (Plin. Nat. 34.59). Pliny also refers to the use of “blacksmith’s water from the shop” (aquae ferrariae ex officinis) as part of a cure for epilepsy (Plin. Nat. 28.58). But Pliny never associates forge water with a ferrugineus taste nor does he describe the Tungri waters as aquae ferratae or aquae ferrariae. However, the suggestion of Scribonius Largus that certain spring waters had the same properties as the irony potion and the suggestion of Seneca that the taste shows the quality tends to support some kind of connection between Pliny’s ferrugineus sapor in Tungri waters and the potion prepared from red-hot iron. One suspects that knowledge of the particular spring that Scribonius described or knowledge of an entire category of mineral waters called aquae ferratae might have been part of the general knowledge of Pliny’s world that could have influenced him or his informant on the taste of the Tungri waters. [40]

Ferri flos?

By ferrugo, Pliny did not seem to refer to the pieces of black oxide that come off in the water when a red-hot iron or steel is quenched in water because in discussing a similar phenomenon with copper/bronze, Pliny had a distinct name for these pieces of oxide. He called them flos (“flower”). Pliny’s description of the flos of copper/bronze falling off the red-hot metal spontaneously after it is quenched is an accurate description of what happens to the brownish/blackish cupric oxide coating that develops on copper when it is heated to a red-hot temperature and then quenched in water.[41] Unfortunately, while he gave a lot of attention to aeris flos (“flower of copper/bronze”), Pliny never once mentioned ferri flos (“flower of iron”).

Yet, intriguingly, Pliny does mention squama ferri (“scales of iron”) which would seemingly be closely related to ferri flos (Plin. Nat. 34.61). In discussing copper/bronze, Pliny notes squama aeris (“scales of copper”) are detached from cakes of red-hot copper/bronze by hammering rather than fall off spontaneously (Plin. Nat. 34.40). Pliny’s description suggests that his squama ferri is the same as what blacksmiths call “hammer-scale”. But archaeologists who study historical metallurgy have concluded that there is no real difference between the “small (typically 1-3 mm) fish-scale like fragments of the oxide/silicate skin” that come off from hammering due to mechanical shock and those that fall off spontaneously on quenching due to thermal shock. They are both predominantly black iron (II, III) oxide.[42] Surely, if Pliny could conceive of an aeris flos and squama ferri, he must have been able to conceive of a ferri flos. Upon cooling both squama ferri and ferri flos would take on the same blackish color.

But it seems for Pliny and other Romans there was a difference between ferrugo, ferri flos, and squama ferri. The means of preparation was always critical in determining the medicinal virtues of these particular substances. Furthermore, the -ugo suffix suggests a changed state of the iron. Ferrugo was something with regard to the iron that just did not fly or fall off. Just as Pliny describes how aerugo and robigo was scraped off metals, it is highly likely he would have believed that ferrugo had to be scraped off as well.[43] Indeed, not all the iron (II, III) oxide comes off on quenching and blacksmiths often file or scrape off any remaining oxide in preparation for tempering (discussed below). Thus, if ferrugo was associated with the taste of the water, it was because ferrugo was on the quenched iron/steel object that came out of the water, although Pliny and other Romans might not have distinguished between ferrugo, ferri flos, or squama ferri when it came to taste. They might have all tasted ferrugineus since they are all basically black Iron (II, III) oxide.

Strange Color Effects

Most translators of Catullus, Virgil, Ovid, et al. have interpreted most references to ferrugo as emphasizing the color of ferrugo rather than the substance itself or some other characteristic of the substance. They have assumed the term represented some particular hue and have tried to guess what hue that was, variously suggesting red, purple, violet, blue, black, etc. But classical writers when using the word ferrugo, in fact, meant the substance, a substance that had certain properties only one of which was color. These properties of ferrugo could also be described using the adjective ferrugineus. However, taken altogether, the uses of ferrugo and ferrugineus suggest that when it came to color there was something strange going on. Some classical references to ferrugo make quite good sense when ferrugo is seen as imparting a blackish color to the object described. But others do not. So what is going on?

A good example of a case where ferrugo straightforwardly implies a blackish color is Albius Tibullus (ca. 55 BC – 19 BC) who depicts the color of an approaching storm as that of pitch-black ferrugo (picea ferrugine caelum).[44]

Another good example where references to ferrugo clearly suggest a black color can be found in Catullus (ca. 84 BC – ca. 54 BC). Toward the end of his “little epic” poem 64, Catullus recounts the story of Theseus. As Theseus set out to fight the Minotaur he left with a “dark” sail to express his father Aegeus’ sorrow and burning of mind over Theseus’s departure. But Aegeus also sent a bright white sail (candida vela) that he asked Theseus to hoist as a signal when his shipped returned so Aegeus would know that Theseus was safe. As fate would have it, upon his return to Athens after having killed the Minotaur, Theseus forgot to raise the white sail. His father seeing the “dark” sail, thought for sure that Theseus was dead and, in his sorrow, Aegeus committed suicide by leaping into the sea.

Catullus described this dark sail in some detail.[45] At different points he refers to the sail as stained/dyed/colored linen (infecta lintea), gloomy garments (funesta vestis), and Iberian cambric darkened with ferrugo (carbasus obscurata dicet ferrugine Hibera) (Cat. 64.225-227, 234.) Modern translators and commentators have imagined that these dark sails were red, purple, violet, etc. in color, assuming that some ancient dye must have created such colors.

But with our understanding of ferrugo as black in color all this confusion fades away.[46] A lusterless black color would also put Catullus right in line with the traditional Greek story of Theseus far more than a color like red or purple. The accounts of Diodorus (fl. 60 – 30 BCE), Plutarch (c. 46 – 120 CE), Pausanias (c. 2nd century CE), and the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Appollodorus all consistently use the same wording referring to the “dark” sails as μέλαν (“black”, “dark”) and the “light” sails as λευκόν (“white”).[47] In a more faithful Latin translation than that of Catullus, Gaius Julius Hyginus (ca. 64 BC – AD 17) translated μέλαν ἱστίον into Latin as vela atra. In contrast to the shiny black color of niger, Romans used ater to describe the lusterless black color of charcoal and other burnt objects which would perfectly capture the color effect of ferrugo.[48]

Another rather curious assertion of the blackness of ferrugo is Ovid’s description of Lucifer preceding Caesar’s death. Here Ovid straightforwardly describes ferrugo as atra (“dull black”) in color.

Caerulus et vultum ferrugine Lucifer atra sparsus erat... (Ov. Met. 15.575)

And blue Lucifer [i.e., the morning star, the planet Venus, literally the “light-bringer”] had been sprinkled with dark ferrugo [with respect to] his face.[49]

However, Ovid’s description of Lucifer also suggests that black ferrugo curiously did not make Lucifer appear blackish. Elsewhere Ovid describes Lucifer as bright (clarus) riding his white horse (albo equo) (Ov. Met. 15.189). And yet here Lucifer appears blue, and the sense of the passage is that it is the black ferrugo which is causing Lucifer to appear blue rather than white, definitely an unexpected optical effect for a blackish substance.[50]

Furthermore, the same kind of strange optical effect of ferrugo seems inherent in the way Romans use the adjective ferrugineus which never suggests a blackish color. For example, a black color simply makes no sense in describing the color of Lucretius’ awnings. In his epic poem De rerum natura, Titus Lucretius Carus (ca. 99 BC – ca. 55 BC) uses the atomic theory of the Greek philosopher Democritus to explain how very fine films coming from the surface of an object creates the impression of color in the eyes of the viewer.[51] To demonstrate his point, Lucretius describes the colors of the awnings hanging over Roman amphitheaters:

For we certainly see many objects cast off particles in profusion, not only from deep inside, as I said before, but in fact often from their surface too, such as their colour. The lutea [yellow], russa [red] and ferruginus awnings frequently do this, when they flutter and flap, spread out on poles and beams and stretched across large theatres. For there they add colour to those in the seated areas below, to those with a close view of the stage and to some of the stage itself, forcing the whole theatre to shimmer in their colours–and the more tightly enclosed by its walls a theatre is, the more cheerful is everything inside, robbed of sunlight and bathed in charm.[52]

One can hardly imagine a black awning having the effect that Lucretius suggests.

Thin-Film Interference

These strange optical effects of ferrugo suggests that Romans had in mind what today we call “temper colors”. A thick layer of iron (II, III) oxide that forms on iron/steel brought to a red-hot heat in a charcoal-fired furnace appears very black indeed. But very thin coats of this oxide on iron/steel produce brilliant colors that start becoming visible at temperatures as low as 200°C. At submicron thicknesses of iron oxide, thin-film interference masks the normal black color of the oxide.

Surely Romans were familiar with these colors and were probably fascinated by the temper colors generated by iron and steel just as we are today by the colors formed by the same thin-film interference that causes the iridescent colors on oil slicks, soap bubbles, butterfly wings, and peacock feathers. Indeed, there might have been a demand for iron of such brilliant colors simply for the sake of their beauty. Early evidence of the awareness of these light effects can be found in the writings of Lucretius in the 1st century BCE, Philo of Alexandria in the 1st century CE and Lucian in the 2nd century CE. Although it is not until the 17th century that we start to see a modern understanding of thin-film interference in the writings of Robert Hooke and Isaac Newton, the Romans must have believed that ferrugo had something to do with these colors on iron/steel.[53] They might have seen, for instance, that one could file away the temper colors and what would be left on the file would be a fine black powder, the same black powder that formed on red-hot iron/steel.

Historically more important than sheer beauty, temper colors played an important role in the tempering of steel. Several steps are necessary to produce a good steel tool or weapon. Firstly the smith smelts the ore and produces a bloom of iron. Next he reheats the bloom in a charcoal furnace which carburizes the iron, converting the bloom (or at least the surface of the bloom) from iron into steel. The smith then shapes the red-hot bloom into the form of the tool or weapon he is making and, when finished, quenches the part of the tool or weapon that is to be hardened in water or some other cooling medium. However, if he cools the steel edge too quickly it becomes quite brittle and easily shatters on impact. Thus, after an initial quenching, the smith “tempers” the steel by gradually reheating the tool or weapon until it reaches the proper temperature.

In the days before temperature-controlled ovens, the blacksmith judged when the steel edge had reached the right temperature by polishing the part of the quenched steel tool or weapon that was to be tempered in order to better see the temper colors. As he gradually reheated the hardened steel, he would observe the gradual change in color as the edge got hotter and hotter. When the edge got to the proper color, he would stop heating the tool or weapon and immediately start to cool the tempered steel (typically by a second quenching) in order to “fix” the temper color. Tempering softened the steel, but what the steel lost in hardness it more than offset by gains in toughness.[54]

Fig. 7 Tempering Colors

As the temperature increases, the thickness of the oxide layer increases and the interference colors change in a predictable order. (See Fig. 7.) The system of colors is not foolproof. The thickness increases the longer the steel is held at a certain temperature, so steel held at 400˚F will eventually pass from straw to brown to purple given enough time. The final hardness at a certain temperature is also dependent on the particular type of a steel. An experienced blacksmith learns to take all these variables into account in tempering his steel.[55]

Suggesting that ferrugineus was the color of tempered steel is not new. Indeed, back in 1714, the anonymous editor of Thomas Creech’s translation of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura wrote that ferrugineus was “not the Colour of rust Iron, as some will have it to be : but of smooth and polish’d Iron, after it has been heated in the Fire, and is grown cold again ; as the Buckles we wear in Mourning” which he described as “a violet Colour”.[56]

Making Steel

So what did ancient Romans know about making steel? There is quite clear archeological evidence for carburization and quenching as early as the 12th century BC in the Eastern Mediterranean from a well-preserved pick head found at Mount Adir in Palestine and a dagger blade from Cyprus.[57] Furthermore, there is no better statement of the knowledge of quenching to make iron hard than the classic passage in Homer in which he notes the similarity of the hissing sound as Odysseus thrusts the stake into the great Cyclops Polyphemus’ eye to that of the blacksmith thrusting his red-hot iron into cold water.

ὡς δ᾽ ὅτ᾽ ἀνὴρ χαλκεὺς πέλεκυν μέγαν ἠὲ σκέπαρνον

εἰν ὕδατι ψυχρῷ βάπτῃ μεγάλα ἰάχοντα

φαρμάσσων: τὸ γὰρ αὖτε σιδήρου γε κράτος ἐστίν

ὣς τοῦ σίζ᾽ ὀφθαλμὸς ἐλαϊνέῳ περὶ μοχλῷ. (Hom. Od. 391-394)And as when a smith dips a great axe or an adze in cold water amid loud hissing to treat it—for therefrom comes the strength of iron—even so did his eye hiss round the stake of olive-wood.

Homer quite clearly suggests here that dipping gave the iron κράτος (“strength”), suggesting a comparison to bodily strength. Archaeologists have taken this statement as positive proof that blacksmiths in Homer’s time understood the importance of quenching for the purpose of hardening steel.[58]

One can find continuing references to the power of “dipping” to give some special quality to iron through the centuries in ancient Greece. Instead of the verb βάπτω (“dip”), most later writers, beginning with Sophocles, employed the noun phrase βαφῇ σίδηρος (“iron by means of dipping”) (Soph. Aj. 651). Like Homer, Sophocles suggested dipping made the iron ἐκαρτέρουν (“strong”). Ajax in his determination to commit suicide felt himself weakened by his wife Tecmessa’s pleading that he would leave her a widow and their son an orphan, comparing himself to dipped iron which had been tremendously strong but whose edge had now been weakened.[59] By the time of Aristotle, βαφή began being used as a quality of the iron, not just something done to the iron. Aristotle interpreted βαφή as a quality that could be lost by lack of use in peacetime, just as military states could lose their edge after they have won their empire (Aristot. Pol. 7.1334a). Somewhat differently, Theophrastus referred to βαφή as something akin to the sharpness of the edge that iron tools lose when they get blunted by the heat generated by working in soft woods like the lime.[60]

Where the Greeks only employed one verb βάπτω, the Romans had a host of different verbs for dipping and at least four were actually employed (demergo, immergo, praetingo, tingo) to describe the dipping of red-hot iron.[61] The Romans also often employed these “dipping” verbs in conjunction with the noun lacus, the name they gave to the bath in which the smith plunged the red-hot iron.[62] However, most of the Roman references to dipping seem to be more interested in Homer’s hissing sound (Lucr. 6.149-150; Verg. G. 4.172; Ov. Met. 9.170, 12.278), the vapor emitted (Plin. Nat. 2.47), or the medicinal virtues of water created in this way (discussed above) than any hardening effect due to quenching. Indeed, it does not appear that any of the Roman “dipping” terms came to describe the hardening of steel as did the Greek βαφή. Still the Romans must certainly have been familiar with Greek ideas of hardening through dipping. Some like Lucretius and Pliny do make the link explicit, employing words like duro and conduro to describe the hardening (Lucr. 6.969-970; Plin. Nat. 34.56).

The sense one gets, however, in all of these classical Greek and Roman mentions of dipping is that it is the act of dipping itself rather than the cooling that causes the iron to harden. Pliny quite explicitly assigns the main reason for different kinds of iron produced in different places to the quality of the water in which the iron is dipped. The earliest clear statement of the importance of cooling as implied in the modern sense of “quenching” does not come until the work of Plutarch (46-120 CE).[63]

However, if the Greeks and Romans understood that dipping iron in water hardened the iron, then there is little doubt that they were producing steel because quenching does not harden ordinary iron, only iron sufficiently carburised to become, in effect, steel. Furthermore, unless the steel was quenched, it would not be any harder than cold-worked bronze. (See Fig. 8.)[64]

Fig. 8 Comparative Hardness of Steel and Bronze at Varying Carbon, Tin and Arsenic Contents

The Greeks and Romans had several words which have been taken to refer to steel: χάλυψ (chalybs), i.e., iron produced by the Chalybeans; ἀδάμας (adamas), literally “the hardest metal,” at first otherwise unidentified but later associated with steel (and even later associated with diamond); and στόμωμα (stomoma), referring to the point or edge of the weapon that was produced by βαφή, but later employed as the name of a metal used to make weapons. The Romans adopted similar words from the Greeks like chalybs, adamas, and acies (“edge”).[65]

Ancient Tempering

The Greeks and Romans surely must have practiced some form of tempering following quenching. Red-hot steel that has been quenched and thus cooled to ambient temperature is very hard indeed. But it is far too brittle to be useful for any tool except perhaps a file. Any tool or weapon like an axe or sword that has to take an impact would too easily shatter and be completely useless. Tempering dramatically reduces the steel’s brittleness at the cost of only a slight reduction in hardness. It is only with proper quenching and tempering that steel weapons become superior to the best bronze weapons.[66]

None of the Greeks or Romans in the classical era ever expressed clearly the need to temper quenched steel. There was, however, some recognition that certain conditions could cause iron to be too brittle. Sophocles is the first to suggest this in his play Antigone.

Κρέων

ἀλλ᾽ ἴσθι τοι τὰ σκλήρ᾽ ἄγαν φρονήματα

πίπτειν μάλιστα, καὶ τὸν ἐγκρατέστατον

475σίδηρον ὀπτὸν ἐκ πυρὸς περισκελῆ

θραυσθέντα καὶ ῥαγέντα πλεῖστ᾽ ἂν εἰσίδοις (Soph. Ant. 473-476)Creon

Yet remember that over-hard spirits most often collapse. It is the stiffest iron, baked to utter hardness in the fire, that you most often see snapped and shivered.[67]

Sophocles stressed here how it was excessive baking that caused this problem rather than excessive cooling. Pliny and Plutarch suggested that small iron implements be quenched in oil rather than water in order to prevent brittleness (Plut. De Primo 13; Plin. Nat. 34.56).[68]

That Greeks and Romans never mentioned tempering may suggest that they practiced what has been called “intermittent quenching”. As mentioned above, quenching and tempering are most often described today as a two-step process. But most historians of metallurgy suggest this clear distinction between quenching and tempering did not happen until the twentieth century.[69] Indeed, blacksmiths through the ages have traditionally tempered their steel tools, not through cooling the entire object and subsequent reheating, but through intermittent and partial quenching. Blacksmiths were not trying to harden the entire tool. They only quenched the part of the tool that needed hardening, like the edge of the axe. The hardened part would need to be tempered to reduce the brittleness but the traditional blacksmith did this by first filing or polishing the edge (in order to better see the temper colors) and then letting the residual heat from the unquenched part of the tool spread to the quenched area in a controlled fashion until the appropriate temper color was achieved.[70]

If the Greeks and Romans practiced intermittent quenching to avoid the problem of the brittleness of quickly quenched steel that might easily explain why they only seem to use “dipping” terms in relation to the hardening and strengthening of iron. Unfortunately there is not much in the way of archaeological evidence to support claims for the ability of ancient smiths with regard to intermittent quenching. Indeed, there is only one example of intermittent quenching, but fortunately for us it is an excellent example — an axehead found in Egypt dated to ca. 900 BC.

Back in 1930, Carpenter and Robertson analyzed this Egyptian axehead:

A lugged axehead, dated to 900 BC, had never been used as it was covered with a thin layer of magnetite from the last heating. The carbon content varied from zero in the centre to 0.9% at the blade edge. The whole axe had been quenched from a temperature of 800-900°C, giving a hard martensitic cutting edge. This edge had been tempered by the conduction of heat from the thicker parts of the axe, which had not been cooled to ambient temperature before removal from the quenching liquid. The final hardness, therefore, varied from 70 HB away from the edge, to 444 HB at the edge itself. The result was a first-rate axe correctly heat-treated to the hardness one would expect from an axehead today.[71]

This Egyptian axehead shows that even as early as 900 BC at least some blacksmiths had the ability to produce fine steel tools and weapons through intermittent quenching, tempered to a fine blue color.[72]

That we have no clear Greek or Roman description of the process that would have produced this axehead should not surprise us. High quality steel production is notoriously difficult to pull off. For every successful attempt, archaeologists have found quite a few examples of poor quality steel. Certainly not every blacksmith was capable of producing high quality steel and those who could make it may have wanted to keep that information to themselves. Perhaps blacksmiths’ secrets were, for that reason, quite closely guarded through the ages.[73] But whatever the reason, it was only in the sixteenth century in the writings of Biringuccio and Della Porta that we start to see the widespread dissemination of the knowledge about steel production as part of a wave of literature focused on revealing all the secrets of nature.[74] It is then we find the first written accounts of intermittent quenching.[75] One wonders how many generations of blacksmiths had passed this knowledge down until it was finally reported by Biringuccio and della Porta.

The Armor of Arcen’s Son & Chloreus

The idea of temper colors can help explain a couple of passages — the description of the uniforms of Arcen’s son and Chloreus — in Virgil’s Aeneid that have caused much confusion over the centuries:

stabat in egregiis Arcentis filius armis

pictus acu chlamydem et ferrugine clarus Hibera,

insignis facie,… (Verg. A. 9.581-3)The son of Arcens stands firms in excellent arms, in embroidered cloak and bright with Iberian ferrugo, distinguished in appearance.

and

ipse peregrina ferrugine clarus et ostro (Verg. A. 11.772)

[Chloreus was] bright with foreign ferrugo and ostrum.

Clearly, in referring to ferrugo and Hibera, Virgil is playing upon the passage from Catullus 64 (discussed above), but instead of ferrugo darkening as it does with Theseus’ sail, here ferrugo is brightening. Most interpreters of Virgil have tried to translate ferrugo as a color term referring to some fine dye they imagine could have been used to color Arcen’s son’s chlamys. Isidore of Seville first suggested this back in the 6th century CE, defining ferrugo as the blackish purple color made in Spain that all purple dyers produced in the first dyeing.[76]

However, instead of the black powdery ferrugo darkening the sail as in Catullus, the temper color of a thin layer of ferrugo must be seen as brightening. As we will see below in further analysis of Lucretius’ awnings, sometimes the adjective ferrugineus is indeed used as a color term associated with dyeing, but here Virgil is using ferrugo, not ferrugineus. And the only way that ferrugo could brighten anything on the apparel of Arcen’s son and Chloreus is if Virgil is referring, not to linen or wool, but iron. On linen or wool, the only effect would be to darken, like Theseus’ sail. But ferrugo on iron could produce temper colors that might very well be seen as brightening, not the iron per se, but rather that the whole appearance of Arcen’s son and Chloreus, in the same way that the fine purple associated with ostrum would have brightened the appearance of Chloreus. One imagines that Virgil was thus intending ferrugo to apply not to Arcen’s son’s chlamys, but rather to the cuirass or some other similar piece of iron armor typically worn by Greek and Roman military officers.[77]

That cuirasses were made of iron in the classical era is fully demonstrated by the iron cuirass with gold detail (see Fig. 9) found in Tomb II at Vergina dated to the 4th century BCE which might even have belonged to Alexander the Great.[78]

Fig. 9 Iron cuirass with gold detail from the Tomb of Philip at Vergina, 4th century BC, Thessaloniki, Archaeological Museum

Virgil further plays with Catullus by using Hibera to modify ferrugo, while in Catullus Hibera modifies carbasus. The reference to Hibera is paralleled in the Chloreus passage which refers to peregrina ferrugine (“foreign ferrugo“).[79] The play on Catullus would have been complete if Virgil had used Hibera to refer to Pontic Iberia rather than Hispania as in Catullus, but he does not appear to have gone that far. By the time of Virgil, Hispania was already long famous for its fine steel manufacture.[80]

One can find a far clearer example of the use of ferrugo to describe fine steel in the early third-century CE writings of Tertullian.

Non es diligentior deo, uti tu quidem Scythicas et Indicas gemmas et

rubentis maris grana candentia non plumbo non aere non ferro

neque argento quoque oblaquees sed delectissimo et insuper

operosissimo de scrobibus auro, vinis item et unguentis pretiosissimis

quibusque vasculorum prius congruentiam cures, proinde perspectae

ferruginis gladiis vaginarum adaeques dignitatem, deus

vero animae suae umbram, spiritus sui auram, oris sui operam,

vilissimo alicui commiserit capulo et indigne collocando utique

damnaverit. (De Resurrectione Carnis 6.8)You surely are not more careful than God, that you indeed should refuse to mount the gems of Scythia and India and the pearls of the Red Sea in lead, or brass, or iron, or even in silver, but should set them in the most precious and most highly-wrought gold; or, again, that you should provide for your finest wines and most costly unguents the most fitting vessels; or, on the same principle, should find for your swords of finished ferrugo scabbards of equal worth; whilst God must consign to some vilest sheath the shadow of His own soul, the breath of His own Spirit, the operation of His own mouth, and by so ignominious a consignment secure, of course, its condemnation.[81]

We have already mentioned above how Tertullian described some natural waters as ferruginantes, a name that likely reflected some similarity to the waters in which blacksmiths quenched their red-hot iron. But here, quite clearly, Tertullian is using ferrugo as a metaphor for tempered steel which blacksmiths would have produced via that quenching.[82]

The Case for Dark Blue

Even if we acknowledge that the Greeks and Romans understood the concept of intermittent quenching, the question remains what color would they have associated with the final product? Depending on its thickness, the oxide layer could generate many different colors.

Unfortunately, the Greeks and Romans never clearly described temper colors or even the color of steel in their writings. As with tempering in general, however much blacksmiths might have known in classical times, it is not until the sixteenth century that we begin to have explicit recommendations of temper colors.[83]

Modern blacksmiths note that there are no hard and fast rules for temper colors. The proper temper color is affected by numerous factors and a good smith learns to go by results rather than hard and fast rules about color.[84] It is also quite clear that different observers identify different colors or use different names for the same colors. Also the temperatures associated with each color vary greatly from author to author. Some recognize that there are really an infinite number of colors through which the steel passes in tempering and the various “stages” are rather arbitrary.[85]

Perhaps because of all these factors, there does not seem to be much of a consensus on the proper temper color for manufacturing different types of tools and weapons. For example, modern manuals assert that an axe (or more precisely the edge of the axe) should be tempered anywhere from a brown yellow to brown to brown mixed with purple (called “pigeon wing” by some) to purple red to purple to violet to “pigeon blue.”[86]

However, even if there is no single temper color today, it appears as if the Romans had a particular hue in mind when they spoke of ferrugineus in the sense of a temper color. And that color is what today we would call “steel blue”, fairly synonymous with the dark blue color that the Romans otherwise called caeruleus.

Unfortunately, as helpful as Pliny was with ferrugo, Pliny is of little help here because his two references to a ferrugineus color — a mythical bird called the tragopan and a spotted lizard — are too obscure to identify with any particular hue (Plin. Nat. 10.69, 29.45). But stating that ferrugineus was synonymous with caeruleus is certainly not new. Nonius Marcellus, a Roman grammarian back in the 4th or 5th century CE, said the same thing. Over the centuries others have supported this view based on their interpretation primarily of Plautus and Virgil.[87]

Perhaps in this respect, the ancients were no different than moderns because, of all the possible temper colors, the one today most closely associated with steel is blue. Writers since the 1800s regularly employ phrases like “cold blue steel” and “steel blue” but you will find nary a reference to “cold purple steel” or “steel purple” or any other temper color. This popular association between steel and blue goes back to the nineteenth century and actually led to a fad of finding evidence of ancient knowledge of steel in anything “blue.” Thus, well before archaeologists discovered the blue axe in Egypt mentioned above, there was a general consensus that various tools, weapons, helmets, etc., painted blue in ancient Egyptian drawings were made of steel.[88]

There was also a general consensus among 19th-century scholars that Homer’s Greeks knew blue steel by the name κύανος (kuanos).[89] Heinrich Schliemann originally accepted this equation of kuanos with blue steel, but following the critique of Karl Richard Lepsius, Die Metalle in den Ägyptischen Inschriften (1871) and Wolfgang Helbig, Das Homerische Epos (1884) and Schliemann’s own findings of a frieze adorned with blue glass at Tiryns, he ended up rejecting this equation of blue color with steel.[90] Other scholars in the 1880s and 1890s reached a similar conclusion to Schliemann and by the turn of the century the old consensus was pretty much dead in the water and a new consensus had emerged following Theophrastus in identifying kuanos as either natural lapis lazuli or a cheaper artificial bluish glass.[91] Still even today one can occasionally still find occasional mentions that kuanos in Homer’s Iliad refers to steel.[92]

Nineteenth-century scholars also suggested that Homer’s σίδηρος ἰόεις (sideros ioeis)(“violet-colored iron”) (Il. 23.850) meant tempered steel, in contrast to Homer’s seemingly plainer σίδηρος πολιός (“gray-colored iron”)(Il.9.366; Od.24.168).[93] Although ioeis might more accurately be seen as evidence of a “violet” rather than a “blue” temper, given the close popular association between blue and steel, it is not difficult to understand why sideros ioeis has even quite recently been translated as blue steel. Furthermore, translating ioeis as “blue” is not that far-fetched, since ioeis was one of Homer’s sea colors.[94]

However, making any claim about kuanos or sideros ioeis in Homer will always be rather tenuous. As scholars since William Gladstone have noted, the early Greeks did not see colors as we do today. For instance, early writers like Homer and Sappho never described the sky or the sea as kuaneos (i.e., the color of kuanos). They described the sea as black, white, gray, dark, wine-dark, and purple, but not kuaneos like later Greek writers. Gladstone used this fact to argue that the early Greeks were blue-blind. However, as Götz Hoeppe asserts, modern linguistic analysis has solidly demonstrated that for the early Greeks, including Aristotle, “luminosity was more important than hue in characterizing color.” Thus kuaneos could refer to a color we would interpret as black, blue, or indeed any dark color. What was important to the early Greeks was that “blue bordered on black or dark, and that both of them constituted the dark end of a scale of colors”.[95] Such an explanation helps us understand how, besides iron and the sea, Homer could also write of the “blue” color of Odysseus’ beard and the “violet” color of fleece. And thus it would be very difficult to identify any color term in the writings of Homer, Sappho, et al., as evidence of an understanding of temper colors.

Later Greek writers, however, came to understand kuaneos as a dark blue color, and Roman writers who translated kuaneos into Latin as caeruelus likewise understood the term to mean dark blue. A case in point is Plutarch who treats kuaneos as a temper color in his description of the Spartan Monument of the Admirals at Delphi. The monument was created between 405 and 395 BC to commemorate the naval victory of the Spartans over the Athenian fleet at the Battle of Aegospotami in 405 BC during the Pelopeonnesian War. It consisted of thirty-seven life-size bronze statues representing the Spartan general Lysander, the “admirals” who participated in the battle, and the gods who helped them.[96]

Plutarch in his work The Oracles at Delphi No Longer Given in Verses, written circa 120-125 CE, reported the observations of a young man Diogenianus of Pergamon on these statues. Diogenianus was not too struck by the artistic merit of the statues but he admired the color of the bronze which was not like typical rust or verdigris. Rather the statues shone with a blue dye (βαφῇ δὲ κυάνου), which gave the admirals a nice touch being the color of the sea (θαλαττίους) at its deepest depths. Diogenianus wondered whether ancient artisans had some special means of preparing bronze akin to the tempering (στόμωσις) of swords (ξιφῶν) that had been forgotten and thus led to the end of the use of bronze in war (Plut. De Pyth. 2). Plutarch used the phrase βαφῇ δὲ κυάνου (“kuanos by means of dipping”) to describe this dark blue color, closely akin to Sophocles’ phrase βαφῇ σίδηρος (“iron by means of dipping”) and strongly suggesting tempering a dark blue color by means of intermittent quenching.

Charon’s Boat

Accepting dark blue as the main referent for tempered steel also helps resolve one of the most famous points of confusion in classical literature: What exactly is the color of Charon’s boat that ferried the dead over the river Acheron in Virgil’s Aeneid? In one passage, as Aeneas approaches the river, Virgil describes Charon’s boat as ferruginea cymba (Verg. A. 6.295). However, in a later passage, when the golden bough is displayed, Charon steers his boat towards Aeneas and this time Virgil describes the boat as caeruleam puppim (Verg. A. 6.384). The question how the boat could possibly be both ferrugineus and caeruleus has befuddled scholars for centuries. But if one understands that ferrugineus was synonymous with caeruleus, all this confusion fades away. Assuming a dark blue color also reconciles Virgil with earlier Greek writers like Leonidas, Theognis, and Theocritus who described Charon’s boat as kuaneos.[97] Just as Catullus was being consistent with his Greek sources in using ferrugo to describe the dark sails, so Virgil was also being consistent in translating kuaneos as alternately caeruleus and ferrugineus.

Plautus

One can also find evidence in support of dark blue in the earliest documented appearance of ferrugineus in the Latin language. Titus Maccius Plautus (c. 254 BC – 184 BC) introduced the word ferrugineus in his comedy Miles Gloriosus (“The Boastful Captain”) in the context of an elaborate scheme hatched by the slave Palaestrio to help his former master Pleusicles rescue his girlfriend Philocomasium from the boastful Captain who had absconded with her to Ephesus. In order to trick the Captain, Palaestrio has Pleusicles dress like a shipmaster (nauclerus) who has come to take Philocomasium back to Athens (Pl. Mil. 4.4).[98]

Palaestrio very precisely describes how to dress up in the garb of a shipmaster, saying Pleusicles needs to put on a broad-brimmed hat (causea), a wool patch over his eye, and a cloak (palliolum) fastened only over the left shoulder leaving the right shoulder and arm bare. Then, after describing the garb, Palaestrio tells Pleusicles that with his clothes well girded up, he should pretend as though he was a gubernator (“a ship’s steersman or pilot”). On top of that, Palaestrio tells Pleusicles to get all the things he needs from the house of an old gentleman who keeps (habet) fishermen (piscatores). By using the word habet, Plautus suggests that the fishermen may be slaves of the old gentleman.[99]

Furthermore, Palaestrio specifies the exact color of both the hat and cloak as ferrugineus. As an aside to explain why he wanted the outfit to be ferrugineus, Palaestrio explains “because it [ferrugineus] is the thalassicus color.” Here Plautus is clearly Latinizing the Greek work θαλάσσιος meaning “of, in, on, or from the sea.” Thus Plautus is suggesting that ferrugineus was a color associated with the sea.

Most commentators and translators have suggested that by thalassicus, Plautus was referring to a seaman and not the sea per se, and thus ferrugineus represented the color of a typical seaman’s clothing.[100] Translating the passage as a typical seaman’s color does make logical sense. After all the purpose of the disguise is to fool the Captain into thinking that Pleusicles is really a skipper, so of course he should wear clothing of a color that a seaman would wear. And, indeed, sometimes the Greek term thalassios did refer to the seaman rather than the sea, as seen in the writings of Herodotus and Thucydides.[101] However, since no scholar today has any clue what color seamen wore in Plautus’ time, it has been anybody’s guess as to what color he meant by ferrugineus which inevitably has given rise to the confusing array of modern translations mentioned at the beginning of this paper.

While translating thalassicus as “seaman” makes logical sense, one can also easily imagine that there is something decidedly “funny” about this passage. A recent study by Michael Fontaine is very aptly titled Funny Words in Plautine Comedy.[102] Plautus loved playing with words. Why go for logic when you could go for humor!

The device of having a character disguise himself as a shipmaster was a long tradition in Greek comedy (e.g., Soph. Phil. 123). Plautus himself mentions in passing the same ruse in Asinaria (“The Ass-Dealer”) (Pl. As. 1.1).[103] Plautus in Miles Gloriosus was obviously having some fun with this tradition. One can imagine that there is something in the description of the ship-master’s clothing that is supposed to be funny. Indeed, it is likely that Palaestrio is deliberately distorting the description of a shipmaster so that the rather stupid Pleusicles would not look like a shipmaster. As Robert Edgeworth well noted — in defending his argument that ferrugineus referred to the red color of a typical seaman’s uniform — there was no need to assume that the advice that Palaestrio gave to Pleusicles had to be good advice. “Indeed, the bland acceptance of howlingly bad advice, based on information which the audience will recognize as faulty, is stock and trade of the comedy of any age”.[104]

For instance, the notion that slave fishermen would wear the same uniform as shipmasters suggests something funny was up. Perhaps there was also something funny in the description of the outfit itself. The way that Palaestrio tells Pleusicles to do up his palliolum seems quite typical of the garb of “seamen” as seen in depictions of Charon and Odysseus in art after the 4th century BCE. But there is something strange in describing the hat that Pleusicles is supposed to wear as a causea, which is a Greek word (καυσία) referring to a hat particularly identified in Hellenistic times with the region of Macedonia. The hat shows up in so many statutes and coins from Macedonia and is so readily distinguishable from other hats that there is no doubt what the causea looks like.[105] (See Fig. 10.) In contrast, depictions of people associated with the sea seem to almost uniformly wear a very different conical cap called the pilos.[106](See Fig. 11.)

Fig. 10 Terracotta Statue of Macedonian Man Wearing a Causea

Fig. 11 Greek terracotta head topped by a pileum c. 5th Century BCE

Plautus may very well have also intended something funny with regard to the color of the disguise. It is not that the words ferrugineus or thalassicus by themselves were funny or that asserting that ferrugineus was colos thalassicus was funny. Indeed, the Roman audience would have understood that, rather than a typical seaman’s color, by thalassicus Plautus was actually referring to the sea and they would have actually understood that ferrugineus was indeed a color of the sea.

The humor came in suggesting that a shipmaster should wear the color of the sea, as if a modern playwright would suggest that an airplane pilot should wear a sky-blue uniform because it was the color of the sky. Or perhaps the humor lay in the suggestion that the captain was trying to claim some link to the sea gods who were typically depicted as dark blue. At least that is what Sextus Pompeius intended after his great naval victory over Octavian at the Battle of Messina in 37 BCE, when he exchanged the purple cloak typical of Roman commanders for a dark blue one to demonstrate that he was the adopted son of Neptune.[107] If ferrugineus was a color of the sea in a Roman sense, then it must have been fairly synonymous with caeruleus because that was practically the only adjective that the Romans seem to have applied to the color of the sea in the Roman Republic and afterwards.[108]

Lucretius’ Awnings

Lucretius’ intent was quite different from the comedic intent of Plautus. For the purposes of his didactic poetry, we must presume his ferruginus was an actual color produced by an actual dye used on the linen awnings and must have been a commonly understood name for a particular color in his time. As for what color Lucretius might have meant by ferruginus, we can certainly say that the color was distinct from lutea and russa in terms of hue since he represents them as three distinct hues. Beyond that it would be hard to go. But certainly substituting caeruleus for ferruginus would not cause any difficulties. Several translations and commentators have indeed suggested “blue” or “dark blue” as the intended meaning of ferruginus in Lucretius.[109] Still we can go farther than suggesting that dark blue is simply plausible.

Several circumstantial pieces of evidence actually suggest a dark blue color. Writing a century after Lucretius, Pliny also commented extensively on the use of dyed linen awnings in the theatres, observing that a reddish (rubent) and a “sky” color (colore caeli) were popular during Nero’s reign for these awnings. The phrase colore caeli (“color of the sky”) in Roman times was well understood to represent a dark color equivalent to caeruleus, not the light blue color that we today typically associate with “sky blue” today. Caeruleus was a color used just as often to describe the sky as it was to describe the color of the deep blue sea. Roman poets used the color to describe the color of the sky raining heavily or heralding rain, storm clouds, and the most watery part of the rainbow.[110] Indeed, etymologists going back to the nineteenth century have long asserted that caerulus was actually derived from caelulus — the adjectival form of caelum (“sky”) — due to the difficulty of pronouncing the l-l combination, a classic example of what linguists call “dissimilation”.[111] Caeli caerulus (“the blue of heaven”) had become a rather stock phrase well before Lucretius. Quintus Ennius (239-169 BCE), often considered the father of Roman poetry, in his Annales introduced the phrase caeli caerula templa (“the blue vault of heaven”), a phrase that was later used by Cicero, Varro, and other writers. Lucretius used the phrase caeli caerula three times (Lucr. 1.1090; 6.96; 6.482) and Ovid repeated it in Metamorphoses (Ov. Met. 14.814) and again in Fasti (Ov. Fast. 2.487).[112] Pliny further supports a dark rather than light blue interpretation in his comment that stars were drawn on these awnings to represent a night sky (Plin. Nat. 19.6). Thus Lucretius’ ferruginus awnings could very well be the same as Pliny’s sky-colored awnings.

The trio of yellow, red, and blue also brings to mind the theory of primary (subtractive) colors (see Fig. 12) which became so prominent in Europe beginning around 1600.[113] Rolf G. Kuehni credits Chalcidius back in the 4th century CE with the first definitive statement of a theory of three chromatic colors between albus (white) and niger (black). But it is curious indeed that Chalcidius, writing four centuries after Lucretius, could posit almost the exact same three colors — pallidus (pale yellow), ruber (red), and cyaneus (blue).[114]

Fig. 12 Traditional RYB color star

However, there is a far simpler explanation for the prominence of the trio of red, yellow, and blue than the suggestion of some universal theory of color ordering. The fact is that these three colors long represented the cheapest dyes for large-scale dyeing available in Europe: madder (Rubia tinctoria) red, woad (Isatis tinctoria) blue, and weld (Reseda luteola) yellow. Indeed these three dyes would continue to be the mainstay of the European dyeing industry from ancient times until replaced in the nineteenth century by synthetic substitutes and they still remain very popular with home dyers today.[115] Woad, called isatis in Greek, was most closely associated with the color κύανεος.[116] Vitruvius (7.14) noted that the equivalent Latin word for this blue dye was vitrum, while Pliny (Nat. 22.2, 35.27) claimed that the Celts called it glastum which seems to derive from the Celtic word glas (“blue”) that later evolved into our modern word “glass”.[117]

One of the biggest areas of confusion in defining the hue associated with ferrugineus has centered around the plant that the Romans called hyacinthus. The basic problem is that Virgil in a passage from the Georgics refers to ferrugineos hyacinthos (Verg. G. 4.183) while in another passage from Eclogue 3 he describes the plant as suave rubens hyacinthus (Verg. E. 3.63). In addition, in Eclogues 2 & 10, Virgil describes the vaccinium — which scholars believe was a Latinization of huakinthos — as niger (“dark/black”)(Verg. Ecl. 2.18, 10.39).

Just as with Charon’s boat, scholars have tried to reconcile these descriptions by assuming that they all represent the same hue. Indeed, they have used the example of the hyacinthus to justify defining ferrugineus as a purple color. Very likely by suave rubens (literally “sweetly reddening”) Virgil did indeed intend a purplish color. In Eclogue 4, he has a similar phrase suave rubenti murice (Verg. E. 4.43-44) which suggests the hyacinthus was the famous reddish-purple of the dye extracted from the murex sea snail. Virgil also refers to the grape as reddening (rubens uva) (Verg. E. 4.29) which we can presume refers to how the grapes transform from a light green to a reddish-purple color. Furthermore, Ovid clearly describes the hyacinthus as purple (Ov. M. 10.213) and Vitruvius, Ovid, and Pliny all consistently describe the vaccinium as purple.[118]

But scholars are wrong to assume that purple was the only color of hyacinthus and that ferrugineus thus had to be purple. Some light may be thrown on Virgil by looking at the writings of Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (4 CE – ca. 70 CE), author of De Re Rustica, the most important source on the agriculture of the Roman Empire. Besides Virgil, Columella is the only other writer who described the hyacinthus as ferrugineus. He actually used four different terms to describe the color of the hyacinthus. In the Tenth Book of De Re Rustica, Columella — inspired by Virgil’s comment in the Fourth Book of Georgics that he would leave discussion of horticulture to some later poet — took up Virgil’s challenge and wrote the entire book in dactylic hexameter. Here Columella tells farmers that they should plant various flowers in the spring including the hyacinthus, either niveus (“snow-white”) or caeruleus (“dark blue”) (10.100). Later in the Tenth Book he writes about rustics with hardened thumbs cropping tender flowers, filling white woven rush baskets with ferrugineus hyacinthus (10.305).

Columella obviously borrowed the phrase ferrugineus hyacinthus from Virgil. But there is nothing in Columella to suggest he conceived of this plant as purple-colored. Indeed evidence from Book Nine in which Columella devotes much attention to beekeeping suggests that ferrugineus was only a synonym for the caeruleus variety of hyacinthus. In the preface to the section on beekeeping, he acknowledges his debt to the earlier writers on apiculture, namely Hyginus, Celsus, and Virgil. Indeed, Book Nine is filled with quite extended passages from Virgil’s account of beekeeping in the Georgics, usually with full credit given to Virgil, but sometimes not. (Cf. G. 4.63; Col. 9.8.13.) Even when Columella is not directly quoting Virgil to embellish his prose, he clearly was heavily indebted to the “scientific” content of Virgil. Columella mentions almost every single one of the twenty or so plants that Virgil suggests were good for promoting honey production in bees. However, Columella also takes quite a few liberties, adding and subtracting detail in much of what he takes from Virgil.[119]

Case in point is what Columella does with hyacinthus. Whereas in the Georgics, Virgil wrote ferrugineos hyacinthos (G. 4.183), Columella wrote caelestis luminis hyacinthus (Col. 9.4.4) by which most modern commentators believe he intended something like “hyacinth of the color of heavenly light” or more simply “sky-blue”. Columella used caelestis mostly in the context of the phrase caelestis aqua (“heavenly water”, i.e., rain), although he also mentioned “heavenly things” (rerum caelestium) and “heavenly honey” (caelestia mella) as well as heavenly light. In the Tenth Book, Columella employed lumen similarly to describe “the yellow-colored light of marigolds” (flaventia lumina caltae) (Col. 10.97).[120] By the color of the sky, Columella undoubtedly meant the color of the dark sky. As mentioned above in the discussion of Lucretius’ awnings, the sky in classic Roman literature was always depicted as a dark blue. Thus, in the final analysis, Columella seems to suggest that there were only two varieties of hyacinthus — deep blue and snow white. Ferrugineus, caeruleus, and caelestis luminis were are all synonyms for this deep blue color.

As to why Virgil employed different colors for hyacinthus, the main reason seems to be — not his botanical interest in different varieties of the plant or poetic license — but rather the colors used in the original Greek sources he was using as his reference. For example, Eclogue 3, in which Virgil uses the phrase suave rubens, seems indebted to some Hellenistic poet who referred to the huakinthos in the same way, most likely as either porphuros or with some other suggestion of similarity to the color of murex dye.

Menalcas

Et me Phoebus amat; Phoebo sua semper apud me

munera sunt, lauri et suave rubens hyacinthus. (Verg. E. 3.62-63)Phoebus Apollo loves me, his gifts, the laurel and the sweetly blushing hyacinth, are always near me.